The Grand Canyon is not only a geological wonder but also a climatic puzzle, where weather conditions shift dramatically depending on elevation, season, and geographic location. From the scorching desert heat of the Inner Canyon to the snowy, forested rims, understanding these variations is essential for visitors, researchers, and conservationists alike.

This article explores the unique weather dynamics of the Grand Canyon, breaking down how temperature, precipitation, and seasonal changes vary between the South Rim, North Rim, and the Colorado River at the canyon’s base. We examine extreme temperature differences—which can exceed 30°F (16.7°C) between the rims and the river on any given day—along with the monsoon season’s impact and the risks of flash flooding, heat exhaustion, and sudden winter storms.

Beyond practical implications for hikers and adventurers, this article also considers the broader environmental picture. How does climate change affect seasonal weather patterns in the canyon? What can historical data and Indigenous knowledge tell us about long-term climatic trends?

By bridging meteorological data with practical insights, this article serves as a comprehensive guide to navigating the Grand Canyon’s unpredictable climate, ensuring visitors and nature enthusiasts are better prepared for one of the most breathtaking yet extreme landscapes on Earth.

Why Weather Matters in the Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon is one of the most iconic natural wonders in the world, attracting millions of visitors each year. Carved over millions of years by the Colorado River, its vast geological formations and extreme elevation changes create a diverse range of climates within a relatively small area. While most people associate the Grand Canyon with arid desert conditions, the reality is far more complex. The canyon is home to multiple microclimates, ranging from high-altitude alpine environments on the North Rim to extreme desert heat at the bottom.

For visitors, understanding these weather variations is not just a matter of curiosity—it’s a crucial safety consideration. The Grand Canyon’s climate can be harsh and unpredictable: scorching temperatures in the Inner Canyon can exceed 120°F (49°C) in summer, while the rims can see heavy snowfall and subzero temperatures in winter. Flash floods, sudden storms, and extreme temperature swings between day and night make weather awareness essential for hikers, rafters, and outdoor enthusiasts.

Beyond its practical implications for tourism, the canyon’s climatic diversity also plays a key role in its ecosystems, geology, and long-term environmental sustainability. Understanding how the weather works in the Grand Canyon can help researchers track the effects of climate change, inform conservation efforts, and preserve this breathtaking landscape for future generations.

Geography and Topography: The Forces Shaping the Canyon’s Weather

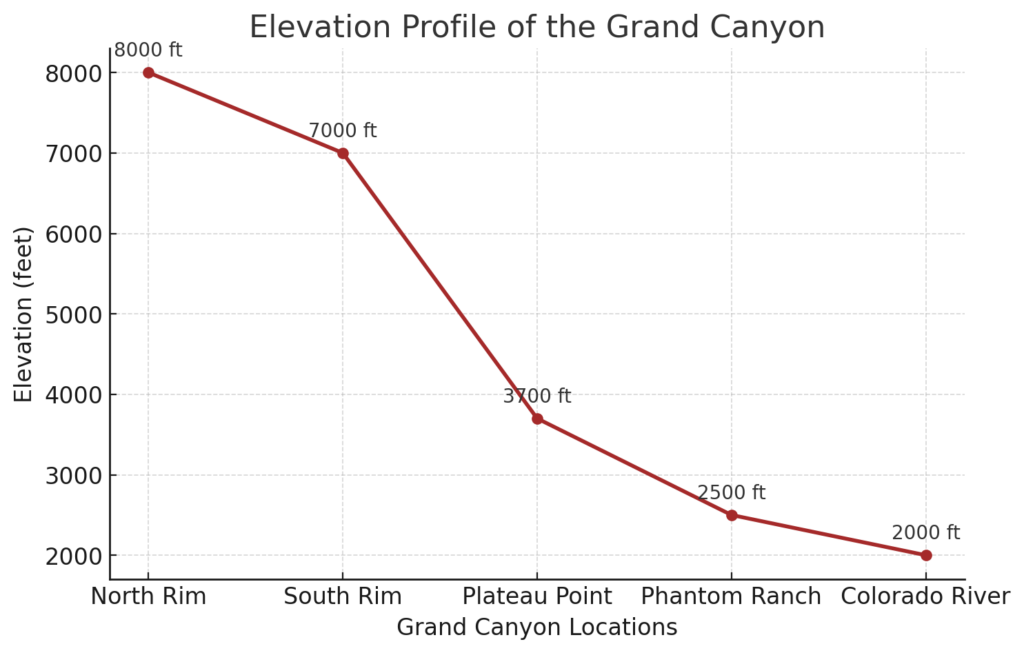

The Grand Canyon’s unique climate is shaped by a combination of geographic location, elevation changes, and topographic features. Situated in northern Arizona, the canyon spans approximately 277 miles (446 km) in length, with elevations ranging from 2,000 feet (610 m) at the Colorado River to over 8,000 feet (2,440 m) at the North Rim. This extreme difference in altitude creates distinct climatic zones, with temperature and precipitation varying significantly between the canyon floor and its rims.

Several key geographical and topographical factors influence the Grand Canyon’s weather:

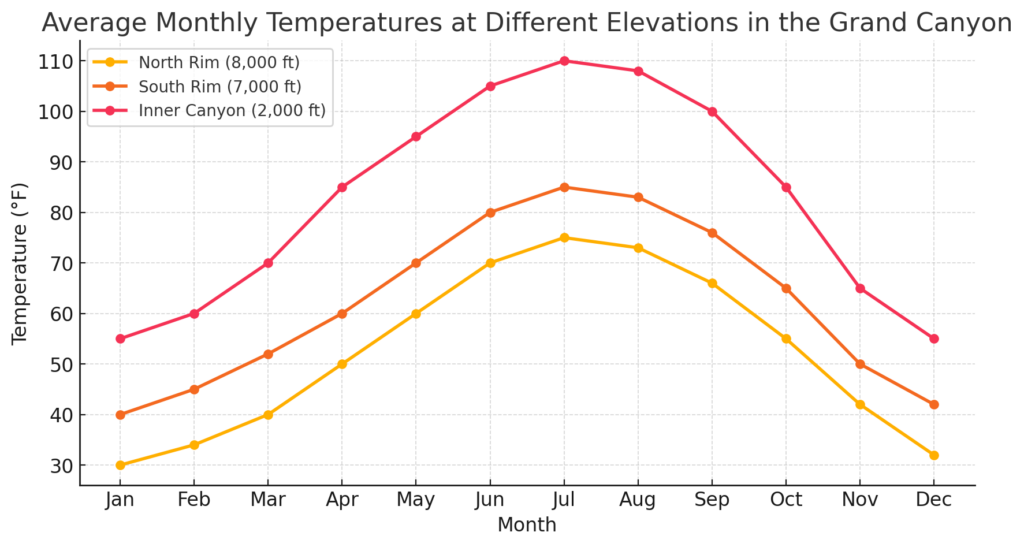

- Elevation: The higher the elevation, the cooler the temperature. For every 1,000 feet of elevation gain, the temperature drops by approximately 5.5°F (3°C).

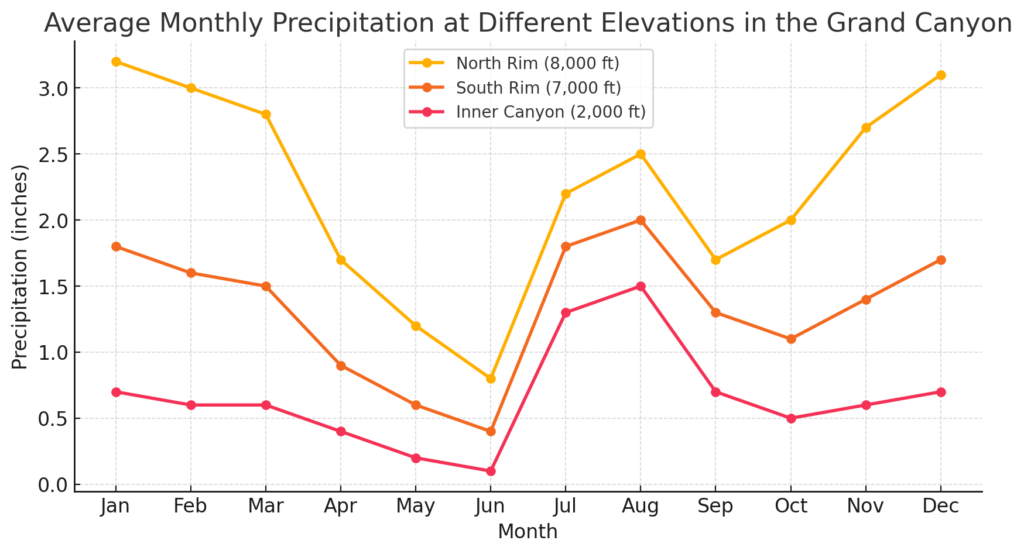

- Rain Shadow Effect: The canyon’s location on the Colorado Plateau means it is partially shielded from Pacific moisture, resulting in relatively low precipitation levels. However, the North Rim receives significantly more rain and snow than the South Rim due to its higher elevation.

- Temperature Extremes: The Inner Canyon acts as a heat trap, where sunlight absorbed by rock walls raises temperatures dramatically, leading to scorching conditions during the day and rapid cooling at night.

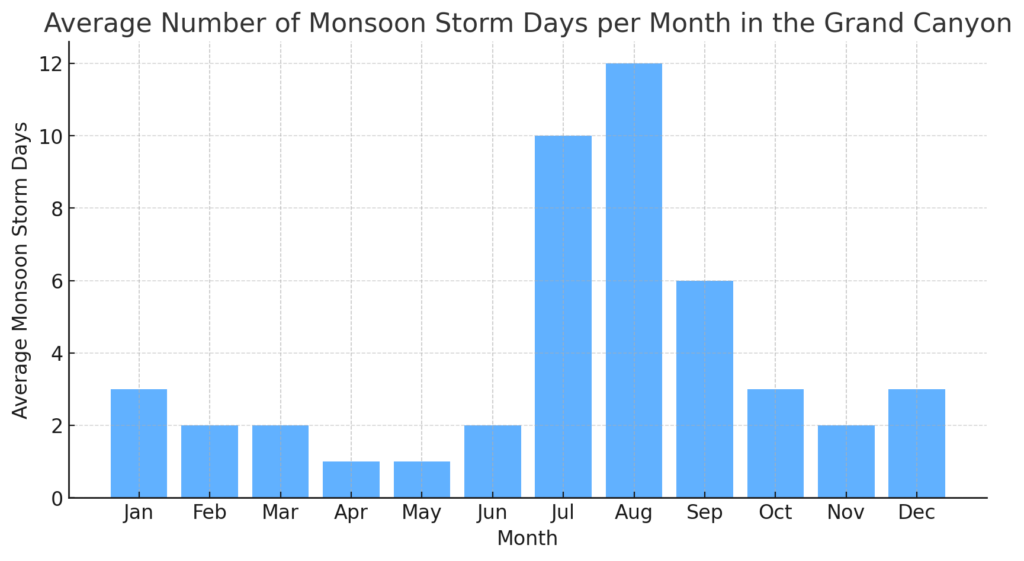

- Monsoonal Influence: From July to September, the North American Monsoon brings sudden, intense thunderstorms that can cause dangerous flash floods in slot canyons and low-lying areas.

These factors make the Grand Canyon’s weather both fascinating and highly unpredictable, requiring careful study to fully understand its patterns and effects.

The Role of Elevation and Microclimates

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Grand Canyon weather is how much it varies depending on where you are in the canyon. The concept of microclimates—localized weather conditions that differ from the surrounding area—is especially relevant here.

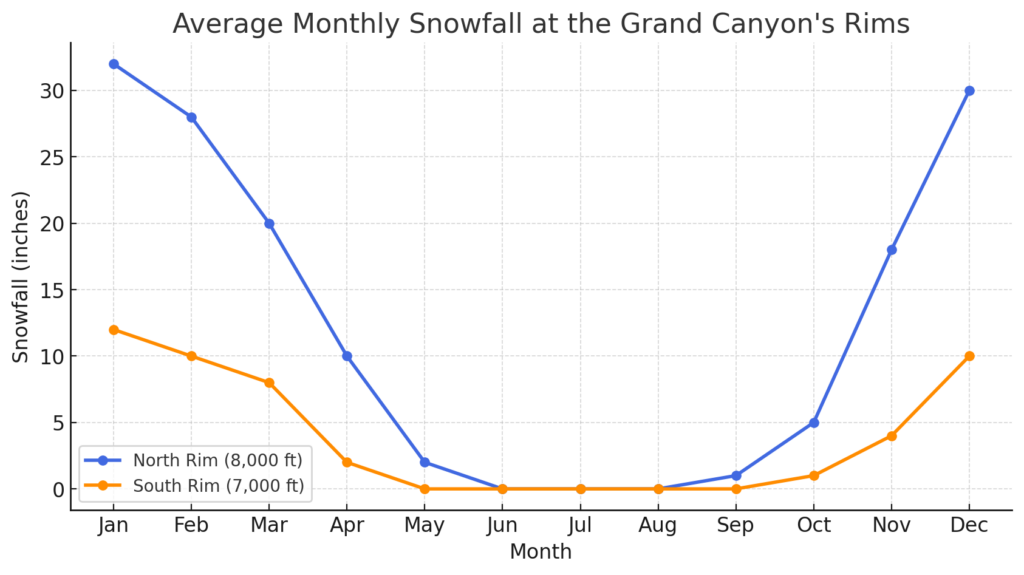

- North Rim: At over 8,000 feet, the North Rim experiences a cool, alpine-like climate, with winter snowfall exceeding 140 inches (355 cm) annually. It is closed to visitors from late fall to spring due to heavy snow accumulation.

- South Rim: At 7,000 feet, the South Rim is cooler than the canyon floor but warmer than the North Rim, making it the most visited area year-round. It receives about 60 inches (152 cm) of snow per year.

- Inner Canyon (Phantom Ranch/Colorado River): Sitting at about 2,400 feet, the bottom of the Grand Canyon is a true desert, with summer temperatures regularly surpassing 100°F (38°C) and winter temperatures staying mild.

These altitude-driven differences are so extreme that a hiker can experience the equivalent of traveling from Canada to Mexico in a single day, moving through vastly different climates as they descend into the canyon.

This article aims to explore the following key questions about Grand Canyon weather and climate dynamics:

- How do temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather events vary across different elevations within the Grand Canyon?

- What seasonal weather patterns should visitors be most aware of, and how do they impact hiking, rafting, and outdoor activities?

- How does the canyon’s geography influence its microclimates, and what role does topography play in shaping local weather?

- What are the long-term implications of climate change on the Grand Canyon’s weather, water availability, and ecosystems?

By addressing these questions, this article seeks to provide a comprehensive, science-based look at Grand Canyon weather, offering practical insights for travelers while also examining broader environmental concerns.

Geographical and Climatic Context of the Grand Canyon

1.1. The Grand Canyon’s Geographic Position

Latitude, Longitude, and Position in North America

The Grand Canyon is located in the southwestern United States, within the state of Arizona, spanning approximately 277 miles (446 km) in length along the Colorado River. Its geographical coordinates range from roughly 35° to 37° North latitude and 111° to 113° West longitude, placing it within the Colorado Plateau, a region known for its high elevation and arid climate.

This location places the canyon in a transition zone between several major climate systems, including desert, semi-arid, and montane (high-altitude) ecosystems. The canyon’s immense size means that weather conditions can vary significantly across different locations, even within the same day.

Relationship to Surrounding Climate Systems

The Grand Canyon’s climate is influenced by several major regional and global weather patterns, including:

- The North American Monsoon: From July to September, moist air from the Gulf of California and the Pacific Ocean moves inland, triggering intense thunderstorms and flash floods in the canyon.

- Pacific Storm Systems: In winter, storms originating over the Pacific Ocean bring snow and rain to the region, particularly affecting the North Rim and South Rim, which are at higher elevations.

- High-Pressure Systems of the Southwest: During much of the year, high-pressure zones dominate, leading to dry, clear skies and extreme temperature variations between day and night.

- Rain Shadow Effect from the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains: Moisture from the Pacific is partially blocked by these mountain ranges, contributing to the arid conditions of the Inner Canyon.

Due to this interplay of climatic influences, weather at the Grand Canyon is both diverse and unpredictable, with conditions shifting rapidly depending on location and season.

1.2. Topographic Influence on Weather Patterns

Elevation Changes: From 2,000 Feet (Colorado River) to Over 8,000 Feet (North Rim)

The Grand Canyon’s elevation difference of over 6,000 feet (1,800 m) between its highest and lowest points creates dramatic variations in temperature and precipitation. This is one of the primary reasons why the Grand Canyon has such diverse climate zones.

- North Rim (8,000+ feet / 2,400+ meters): The highest and coldest part of the canyon, with heavy snowfall in winter (over 140 inches per year) and cool summers.

- South Rim (7,000 feet / 2,100 meters): Slightly lower than the North Rim, the South Rim experiences milder winters and warmer summers, making it the most accessible and frequently visited part of the park.

- Inner Canyon / Colorado River (2,000–2,500 feet / 600–750 meters): A true desert climate, with summer temperatures exceeding 110°F (43°C) and minimal annual precipitation.

Because temperature decreases approximately 5.5°F (3°C) for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain, visitors often experience vastly different conditions as they hike between the rim and the river.

Rain Shadow Effect and Orographic Lifting

The rain shadow effect is a critical factor in the Grand Canyon’s precipitation distribution. As moist air from the Pacific moves eastward, it is forced upward when it encounters mountain ranges like the Sierra Nevada and the Colorado Plateau. This process, known as orographic lifting, causes the air to cool, condense, and release precipitation on the western slopes of the mountains.

However, by the time this air reaches the Grand Canyon, it has already lost much of its moisture, resulting in low annual precipitation levels in the Inner Canyon and on the South Rim.

- The North Rim, which sits at a higher elevation, receives more precipitation (27 inches / 69 cm per year), supporting forests of ponderosa pines and fir trees.

- The South Rim receives less precipitation (16 inches / 41 cm per year), supporting a more arid landscape with pinyon pines and junipers.

- The Inner Canyon receives the least precipitation (under 10 inches / 25 cm per year), creating a harsh desert environment with cacti, mesquite, and creosote bush.

Impact of Canyon Walls on Temperature Regulation

The Grand Canyon’s steep rock walls play a major role in heat absorption and temperature fluctuation.

- During the day, the canyon walls absorb solar radiation, creating a heat trap in the Inner Canyon. This is why temperatures at Phantom Ranch (near the river) often exceed 110°F (43°C) in summer, while the South and North Rims remain much cooler.

- At night, the stored heat is slowly released, causing significant drops in temperature. In some cases, temperatures can fluctuate by more than 30°F (16.7°C) within a single day.

These rock-driven heat dynamics create microclimates that affect plant growth, animal behavior, and the experience of hikers traveling between different elevations.

1.3. Climate Classification

Köppen Climate Classification Zones Within the Canyon

The Grand Canyon contains multiple climate zones based on the Köppen Climate Classification System, which divides climates into categories based on temperature, precipitation, and vegetation.

- North Rim: Cold Continental Climate (Dsb, Dsc)

- Cool summers and cold, snowy winters.

- Precipitation is relatively high compared to lower elevations.

- Supports dense coniferous forests with firs, spruces, and pines.

- South Rim: Semi-Arid Climate (BSk)

- Hot summers and cold winters with moderate snowfall.

- Lower precipitation levels than the North Rim.

- Supports juniper, pinyon pine, and sagebrush vegetation.

- Inner Canyon: Desert Climate (BWh)

- Extremely hot summers (110°F / 43°C+) and mild winters.

- Less than 10 inches (25 cm) of annual rainfall.

- Dominated by cacti, mesquite, and other drought-resistant plants.

Comparison of Rim, Inner Canyon, and Plateau Climates

The three primary climate zones of the Grand Canyon—Rim, Inner Canyon, and Plateau—exhibit drastically different temperature and precipitation patterns:

| Location | Elevation | Climate Type | Avg. Summer Temp | Avg. Winter Temp | Annual Precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Rim | 8,000 ft (2,400 m) | Cold Continental | 60–75°F (15–24°C) | 10–40°F (-12–4°C) | 27 in (69 cm) |

| South Rim | 7,000 ft (2,100 m) | Semi-Arid | 70–85°F (21–29°C) | 20–50°F (-7–10°C) | 16 in (41 cm) |

| Inner Canyon | 2,000 ft (600 m) | Desert | 95–115°F (35–46°C) | 40–65°F (4–18°C) | <10 in (25 cm) |

This vertical climate diversity makes the Grand Canyon one of the most climatically complex natural landscapes in the world, requiring careful preparation from visitors and researchers alike.

Seasonal Weather Patterns at the Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon experiences dramatic seasonal weather shifts, influenced by its vast elevation range and location within the semi-arid Southwest. Each season presents unique climatic conditions across the South Rim, North Rim, and Inner Canyon, affecting visitor experiences, wildlife behavior, and ecological patterns.

Understanding these seasonal variations is essential for hikers, campers, and outdoor enthusiasts, as weather extremes—ranging from triple-digit summer heat to freezing winter storms—can pose significant challenges. This chapter explores how weather changes through the four seasons, detailing temperature trends, precipitation patterns, and key environmental phenomena affecting the canyon’s diverse landscapes.

2.1. Winter (December – February)

South Rim: Snowfall, Sub-Zero Temperatures, Road Closures

Winter at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon is a season of stunning contrasts—a landscape blanketed in snow, crisp mountain air, and a peaceful quiet rarely found during the crowded summer months. With an elevation of 7,000 feet (2,100 meters), the South Rim regularly experiences snowfall averaging 60 inches (152 cm) per year, transforming the canyon into a winter wonderland. The cold temperatures and icy conditions, however, also create unique challenges for visitors.

During the winter months, daytime temperatures at the South Rim range from 40°F to 50°F (4°C to 10°C), while nights often drop below freezing, averaging lows between 10°F and 20°F (-12°C to -6°C). The air is clear and crisp, offering some of the best visibility of the year, with breathtaking panoramic views of the snow-dusted canyon walls stretching for miles under deep blue winter skies. However, while the beauty of a snow-covered Grand Canyon is undeniable, winter storms can bring hazardous travel conditions, including slick, icy roads, limited visibility, and temporary closures of key access points such as Desert View Drive and Hermit Road.

For those who brave the cold, winter provides a serene and crowd-free experience at one of the most visited national parks in the United States. While popular viewpoints like Mather Point, Yavapai Point, and Hopi Point remain accessible, they are often covered in ice and snow, requiring caution for visitors and hikers. The South Rim Village remains open year-round, offering heated lodges and visitor services, but travelers must be prepared for rapidly changing weather.

Winter also brings changes to wildlife behavior at the South Rim. Mule deer and elk, which are commonly seen in the warmer months, are still present but tend to be less active during extreme cold. Smaller mammals like squirrels and chipmunks retreat to burrows for warmth, while raven and eagle sightings become more common as these birds adapt to the winter landscape.

Despite the cold, hiking is still possible, but extra precautions must be taken. Trails like Bright Angel and South Kaibab become icy and treacherous, requiring crampons or traction devices for safe descent. Rangers strongly discourage attempting rim-to-river hikes in a single day during winter due to shorter daylight hours and unpredictable weather conditions.

Ultimately, the South Rim in winter is a breathtaking yet challenging environment, rewarding well-prepared visitors with some of the most stunning views and peaceful experiences the Grand Canyon has to offer. However, it is not a season to take lightly, as sub-zero temperatures, snowfall, and icy conditions demand careful planning and respect for nature’s power.

North Rim: Heavy Snow Accumulation, Park Closure, Wildlife Adaptations

While the South Rim remains accessible year-round, the North Rim of the Grand Canyon undergoes a complete transformation in winter, effectively shutting down to visitors due to extreme snowfall and hazardous conditions. Sitting at an elevation of over 8,000 feet (2,440 meters), the North Rim experiences some of the harshest winter weather in Arizona, with snowfall averaging 144 inches (365 cm) per year. As a result, the North Rim closes to regular vehicle traffic in mid-November and remains inaccessible until mid-May.

Unlike the South Rim, which retains some visitor services throughout winter, the North Rim’s facilities, including lodges, restaurants, and visitor centers, completely shut down for the season. The roads leading to the North Rim, including Highway 67, are not plowed, leaving access restricted to those who can reach the area via cross-country skiing or snowshoeing. For the small number of winter adventurers and backcountry campers who make the trek, the North Rim offers an unparalleled wilderness experience, with the canyon’s sheer walls and dense conifer forests buried under deep snow.

With the dramatic drop in temperature, which often falls below 0°F (-18°C) at night, the North Rim becomes an inhospitable place for many forms of wildlife. While some species—such as porcupines, bobcats, and mountain lions—continue to roam the forests, others hibernate or migrate to lower elevations. Black bears, which are rarely seen during the warmer months, retreat into hibernation, and many bird species leave the region entirely, seeking milder wintering grounds. The mule deer population, which is abundant during the summer, moves southward to escape the snow, while the hardy Kaibab squirrels remain active, their thick fur helping them survive the cold.

Despite its challenges, winter at the North Rim provides a striking contrast to the rest of the Grand Canyon, offering a landscape that feels more akin to the Rocky Mountains than the arid Southwest. The sight of massive snowdrifts covering the rim and icicles hanging from the canyon’s rocky overhangs presents a perspective that few visitors ever witness. For those willing to brave the elements, the solitude and untouched wilderness make for an unforgettable experience, but preparation is essential. Without plowed roads, emergency services, or shelter, winter travel to the North Rim is reserved only for the most experienced and well-equipped explorers.

While the North Rim in winter remains largely unseen by the general public, it plays a crucial role in the canyon’s ecosystem, serving as a seasonal retreat for animals and a climate refuge that helps sustain biodiversity throughout the year.

Inner Canyon: Mild Daytime Temperatures, Cold Nights, Limited Water Sources

While the rims of the Grand Canyon are blanketed in snow and ice during winter, the Inner Canyon experiences a vastly different climate, making it one of the most intriguing seasonal contrasts in the park. At the bottom of the canyon, near the Colorado River and Phantom Ranch, winter temperatures are much milder compared to the South and North Rims, creating an oasis of relative warmth in an otherwise frigid season. However, this does not mean that winter hiking in the Inner Canyon is without its challenges.

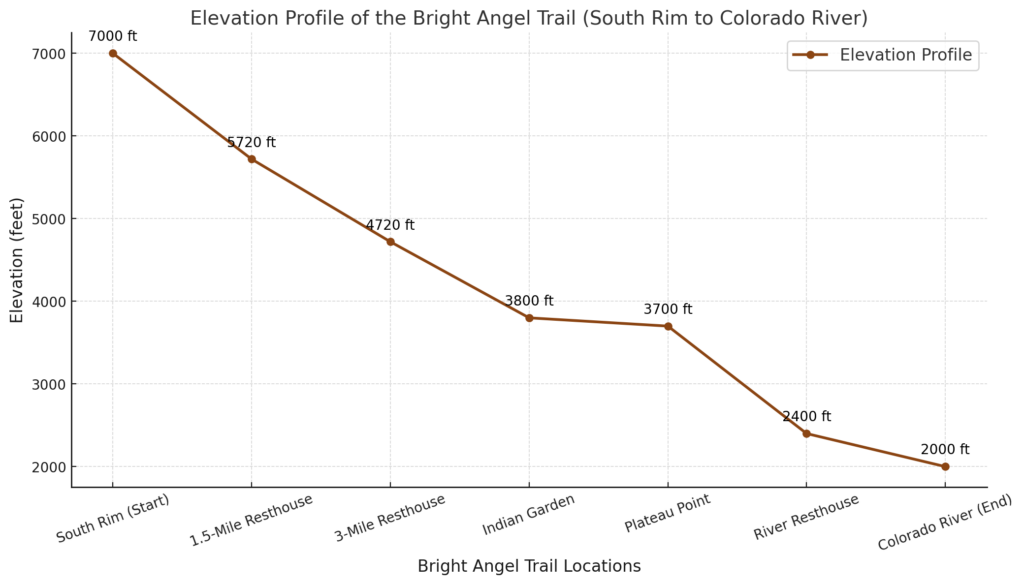

Daytime temperatures at the bottom of the canyon typically range between 50°F and 60°F (10°C to 16°C) from December to February, making it one of the most pleasant times of the year for hiking. Unlike the summer months, when temperatures regularly soar above 110°F (43°C), winter provides a cooler, more comfortable environment for long treks along the canyon’s famous trails, such as the Bright Angel and South Kaibab Trails. This is one of the reasons why winter is considered an ideal season for serious hikers looking to explore the canyon without the risks of heat exhaustion or dehydration that plague summer adventurers.

However, while daytime conditions may feel mild and comfortable, the Inner Canyon undergoes dramatic temperature shifts at night, with lows often dipping below freezing. The absence of cloud cover, combined with the canyon’s deep, open topography, allows heat to escape rapidly, resulting in bitterly cold nights that can catch unprepared hikers off guard. Campers staying at Phantom Ranch or Bright Angel Campground must be equipped with insulated sleeping bags and winter gear, as temperatures can drop to 25°F (-4°C) or lower after sundown.

Another significant challenge for winter hikers in the Inner Canyon is water availability. Unlike the summer months, when the seasonal creeks and springs are more reliable, winter often sees reduced water flow or completely dry creek beds due to frozen sources at higher elevations. Many of the seasonal water stations along the trails are shut off in winter, requiring hikers to carry larger amounts of water or plan refill points carefully. Despite the cooler temperatures, hydration remains a key concern, as dry desert air and exertion can still lead to dehydration.

Wildlife in the Inner Canyon remains active during winter, as many animals prefer the mild conditions of the lower elevations to the harsher, snow-covered rims. Bighorn sheep, mule deer, and ringtails can often be spotted along the canyon walls or near the river, foraging for limited vegetation. Coyotes and foxes remain active, hunting for small rodents, while birds such as canyon wrens and great horned owls continue to thrive in the cliffs and rock ledges.

For hikers and backpackers, winter offers one of the best opportunities to experience the Inner Canyon in near solitude. The crowds of summer and early fall disappear, leaving only the sound of the river and the crunch of boots on the trail. However, proper preparation is essential. Those venturing into the canyon during winter must be ready for both warm and frigid temperatures, limited water sources, and unpredictable weather shifts.

Despite its challenges, winter in the Inner Canyon provides a unique and rewarding experience for those who plan ahead. The combination of mild days, crisp air, and quiet trails makes it a favorite season for serious Grand Canyon hikers, offering a perspective on the canyon that few get to witness.

2.2. Spring (March – May)

South Rim: Increasing Temperatures, Melting Snow, Unpredictable Storms

Spring at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon is a season of transformation, as the harsh winter conditions gradually give way to warmer temperatures, melting snow, and the return of plant and animal activity. However, this period of transition is often unpredictable, as late-season snowstorms, sudden temperature swings, and spring thunderstorms can still occur.

As March begins, the South Rim remains cold, with daytime highs hovering around 50°F (10°C) and nighttime temperatures still dropping below freezing. Snowfall is still possible, particularly in early spring, and lingering ice and snow can make trails hazardous for hikers. However, by April and May, temperatures begin to rise, with daytime highs reaching 60°F to 75°F (16°C to 24°C), bringing more comfortable conditions for visitors.

One of the most significant changes in spring is the melting of winter snow, which leads to increased water runoff and occasional flooding in lower-lying areas. This runoff helps to replenish seasonal creeks and water sources, benefiting wildlife and plant life. However, it also means that some trails may remain muddy and slippery well into April, requiring hikers to proceed with caution, especially on steep sections of Bright Angel and South Kaibab Trails.

Spring is also a time of unpredictable weather shifts, particularly in March and early April. While many days are sunny and mild, sudden cold fronts can bring brief snowstorms or rain showers, catching unprepared visitors off guard. The wind can also be particularly strong during this season, with gusts exceeding 40 mph (64 km/h) at exposed viewpoints.

Despite these challenges, spring is one of the best times to visit the South Rim, as wildflowers begin to bloom, wildlife becomes more active, and visitor numbers remain lower than in the summer months. Animals that were less visible during the winter months begin to emerge, including elk, mule deer, and various bird species, which return to the region as temperatures rise.

For photographers and nature lovers, spring offers stunning contrasts, as snow may still be visible on the canyon’s highest peaks while the lower elevations begin to turn green. The air is clear and crisp, providing excellent visibility, and sunrises and sunsets become particularly vibrant, with the softer spring light casting dynamic shadows across the canyon walls.

As the season progresses into May, the South Rim takes on a decidedly warmer feel, with temperatures reaching the upper 70s°F (25°C). By this time, most of the winter’s snow has melted, and the South Rim’s visitor numbers begin to increase as summer approaches.

Despite its unpredictable nature, spring remains one of the most rewarding times to visit the Grand Canyon’s South Rim, offering a blend of winter’s remnants and summer’s warmth, making it an ideal season for those looking to experience the canyon in its most dynamic state.

North Rim: Late Snowmelt, Delayed Opening, Re-emergence of Flora and Fauna

Spring at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon is dramatically different from the South Rim. While lower elevations begin to warm up by March, the North Rim remains locked in winter conditions well into late April or even early May. Sitting at over 8,000 feet (2,440 meters) above sea level, the North Rim experiences heavy snowfall throughout winter, and it takes much longer for the accumulated snow to melt, delaying the arrival of spring.

As March begins, temperatures at the North Rim rarely rise above 40°F (4°C) during the day, and nighttime lows continue to hover well below freezing. Snow often remains several feet deep, making most trails impassable without snowshoes or skis. This is one of the reasons why the North Rim remains closed to regular visitors until mid-May—road access via Highway 67 is not plowed during the winter months, and lodges, campgrounds, and visitor centers do not reopen until late spring.

The shift from winter to spring is gradual. In April, temperatures begin to climb, and the melting snow gives rise to temporary waterfalls and swelling streams, providing fresh water for wildlife emerging from winter dormancy. Animals such as black bears, mountain lions, and mule deer, which had been largely absent from the North Rim during the peak of winter, return as food sources become available once again. Bird migration picks up, with species such as peregrine falcons, western bluebirds, and red-tailed hawks reappearing along the canyon’s high cliffs and forests.

The late arrival of spring at the North Rim also means that wildflowers bloom much later than they do at lower elevations. While the South Rim and Inner Canyon may already be seeing vibrant displays of desert blooms in March and April, the North Rim’s alpine meadows don’t fully come to life until May or even early June. By this time, lush grasses, blooming lupines, and yellow balsamroot flowers cover the meadows, creating a breathtaking contrast against the remaining patches of snow.

For those planning a visit to the North Rim in late spring, it is important to check road conditions and park opening dates ahead of time. Although the North Rim officially reopens in mid-May, some trails may still be wet, muddy, or even snow-covered, particularly those leading down into the canyon. Early-season visitors should be prepared for chilly temperatures, especially at night, when lows can still dip below 30°F (-1°C) even as the days begin to warm.

Despite the challenges of delayed access and lingering snow, spring is a magical time at the North Rim, as the landscape transitions from a silent, frozen wilderness to a vibrant, green ecosystem. The crowds of summer have not yet arrived, making this an ideal time for solitude and photography, with the melting snow creating stunning reflections in alpine pools and creeks.

By the end of May, the North Rim’s forests, meadows, and canyon overlooks are fully transformed, setting the stage for the short but spectacular summer season ahead.

Inner Canyon: Rapid Warming, Peak Hiking Season Begins

Spring in the Inner Canyon is one of the most favorable times of the year for hiking and outdoor exploration, as it marks the transition from the mild conditions of winter to the scorching heat of summer. Unlike the North Rim, which remains buried in snow well into May, or the South Rim, where winter lingers into March and early April, the Inner Canyon warms up quickly, creating ideal conditions for hikers, backpackers, and rafters navigating the Colorado River.

By early March, daytime temperatures in the Inner Canyon range between 60°F and 70°F (16°C to 21°C), making it one of the most comfortable times of the year for strenuous hikes. The lack of summer’s oppressive heat allows for longer treks without the extreme dehydration risks that come with higher temperatures. Trails such as the Bright Angel Trail and the South Kaibab Trail see an increase in foot traffic, as experienced hikers take advantage of the cooler weather before the heat of summer sets in.

However, nights in the Inner Canyon can still be quite chilly in early spring, with temperatures dropping to near freezing in shaded areas or along the riverbanks. Hikers and campers staying at Phantom Ranch or Bright Angel Campground should be prepared for wide temperature fluctuations, as it is not uncommon for daytime highs and nighttime lows to differ by 40°F (22°C) or more.

One of the biggest advantages of spring hiking in the Inner Canyon is the availability of water. Unlike in summer, when many seasonal springs dry up, spring snowmelt from the North Rim feeds water sources in lower elevations, providing more opportunities for refilling along the way. Streams such as Garden Creek and Pipe Creek run at higher levels, making them more reliable water sources for hikers descending into the canyon. This increase in water availability also supports wildlife activity, as animals including bighorn sheep, mule deer, and desert foxes become more visible along the river and side canyons.

Spring is also the beginning of the rafting season on the Colorado River, as warmer temperatures and increased water flow from melting snow create more favorable conditions for multi-day rafting trips. Though the river remains cold year-round, with water temperatures averaging 50°F (10°C), spring offers some of the best whitewater conditions before the peak runoff of early summer.

By April and May, the Inner Canyon has fully transitioned into warm weather, with daytime highs regularly climbing into the 80s°F (27°C to 32°C). While still manageable, hikers need to begin taking heat precautions, particularly on exposed trails with little shade, such as South Kaibab and Tonto Trails. These increasing temperatures signal the approach of the summer season, when conditions in the Inner Canyon will become dangerously hot for unprepared visitors.

For those looking to experience the Grand Canyon’s backcountry in near-perfect conditions, spring remains the best season to explore the Inner Canyon. Cool mornings, abundant water, and mild afternoons make for comfortable hiking, while wildlife activity, blooming desert plants, and flowing streams add to the experience. However, visitors must still be prepared for rapid weather changes and temperature swings, as storms, high winds, and unseasonably hot days are always a possibility in this ever-changing landscape.

As May gives way to June, the heat of summer begins to set in, bringing an end to the comfortable hiking season. Those who wish to experience the Inner Canyon at its best should take advantage of this short window of ideal conditions before the summer heat takes over.

2.3. Summer (June – August)

South Rim: Warm but Moderate Temperatures, Afternoon Thunderstorms

Summer at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon presents a mix of warm temperatures, bustling crowds, and dramatic weather patterns. While many visitors assume the canyon is unbearably hot in summer, the South Rim’s elevation of 7,000 feet (2,100 meters) keeps temperatures relatively moderate compared to the Inner Canyon. However, this is also the season of the North American Monsoon, bringing sudden and powerful afternoon thunderstorms that can create hazardous conditions for hikers and tourists alike.

In June, the South Rim experiences hot but dry weather, with daytime highs ranging from 75°F to 85°F (24°C to 29°C). Nights remain cool and comfortable, with temperatures dropping to the 40s°F (4°C to 10°C). This period, before the onset of the monsoon, is one of the driest times of the year, making dehydration a risk for hikers. The clear skies and extended daylight hours provide excellent conditions for photography and sightseeing, though the lack of shade along many trails means that even moderate temperatures can feel intense in direct sunlight.

By July and August, the North American Monsoon arrives, bringing moisture from the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California, leading to frequent afternoon thunderstorms. These storms often build rapidly in the late morning, with dark clouds forming over the canyon by early afternoon. The resulting heavy rains, lightning, and occasional hailstorms create spectacular but dangerous weather events, forcing many hikers to pause their treks or seek shelter.

Lightning poses one of the greatest dangers during summer, as the open terrain of the South Rim’s viewpoints and trails leaves hikers and photographers exposed to strikes. Thunderstorms can also cause flash floods in slot canyons and lower elevation areas, with runoff creating hazardous trail conditions. Despite these risks, the monsoon season provides a stunning natural spectacle, with lightning illuminating the canyon walls and waterfalls temporarily forming as rainwater cascades down the rock faces.

Wildlife activity also increases during the monsoon months, as the sudden moisture rejuvenates plant life. Mule deer, squirrels, and various bird species become more active, and the canyon’s plant life, including wildflowers and grasses, flourishes in the wake of the rainfall.

Despite the unpredictability of the monsoon, summer remains the most popular season at the Grand Canyon, with large crowds flocking to the South Rim’s most famous viewpoints, including Mather Point, Yavapai Point, and Desert View. Hotels, lodges, and campgrounds are often fully booked months in advance, and visitor numbers peak in July and early August.

For those planning to visit in summer, it is critical to be prepared for both heat and storms. Early morning hikes provide the best conditions, as temperatures are cooler and the risk of storms is lower. Visitors should also be aware of the potential for rapidly changing weather and avoid exposed areas during thunderstorms.

Overall, summer at the South Rim offers some of the most dramatic and dynamic weather experiences at the Grand Canyon. While heat and monsoonal storms pose risks, they also create breathtaking scenery, unique wildlife activity, and a sense of adventure for those willing to embrace the elements.

North Rim: Cooler Than South Rim, Monsoonal Influence

Summer at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon offers a striking contrast to the intense heat experienced elsewhere in the park. Sitting at 8,000 feet (2,440 meters) above sea level, the North Rim remains significantly cooler than both the South Rim and the Inner Canyon, making it a haven for visitors looking to escape the summer heat. However, while temperatures are milder, summer at the North Rim is still shaped by the North American Monsoon, bringing frequent afternoon thunderstorms and occasional heavy rainfall.

In June, the North Rim enjoys mild and pleasant temperatures, with daytime highs ranging from 65°F to 80°F (18°C to 27°C). Even during the warmest parts of the day, the elevation provides a refreshing coolness, making it an ideal time for hiking and sightseeing. Nights at the North Rim remain chilly, often dipping into the 40s°F (4°C to 10°C), which can be a stark contrast to the sweltering temperatures in the Inner Canyon.

By July and August, the monsoon season is in full effect, bringing daily afternoon thunderstorms that can drop large amounts of rain in a short period. These storms build quickly and dramatically, often forming within hours of the morning’s clear skies. While the rain provides relief from the summer heat and sustains the region’s dense forests, it also creates hazardous conditions for hikers and campers.

One of the biggest dangers during monsoon season is lightning, which frequently strikes the high ridges and open viewpoints along the North Rim. Locations such as Bright Angel Point and Cape Royal, which offer spectacular panoramic views, also leave visitors highly exposed to lightning activity. When storms approach, it is essential to seek shelter immediately, as lightning can strike unexpectedly, even before rain begins to fall.

Another risk during this time is flash flooding, which can turn dry washes and side canyons into raging torrents of water within minutes. Though the North Rim itself is at higher elevation and less prone to direct flash flooding, trails leading into the canyon—such as the North Kaibab Trail—can become dangerous or impassable due to water runoff and mudslides.

Despite these weather challenges, summer remains one of the best times to visit the North Rim, as the cooler temperatures, lush green meadows, and monsoon-driven cloud formations create a breathtaking landscape. Unlike the crowded South Rim, the North Rim receives far fewer visitors, making it an excellent choice for those seeking solitude and less tourist congestion.

Wildlife is especially active during the summer months at the North Rim, as the moisture from the monsoon revitalizes plant life and provides fresh drinking water for animals. Mule deer, wild turkeys, and Kaibab squirrels are commonly seen in the forests of ponderosa pines and aspen trees, while larger predators such as mountain lions remain elusive but present. The monsoon rains also create temporary waterfalls and flowing streams, transforming the landscape into a lush, high-elevation oasis.

For those planning to explore the North Rim in summer, preparation is key. Mornings are ideal for hiking, as temperatures are cooler and the risk of thunderstorms is lower. Visitors should be prepared for rapid weather changes, bring rain gear, and avoid exposed areas during storm activity.

By the end of August, monsoon activity begins to decrease, signaling the approach of autumn. The North Rim’s temperatures remain comfortable, but the days grow shorter, and the first hints of fall color begin to appear in the high-altitude forests.

In many ways, summer at the North Rim offers one of the most pleasant and dynamic weather experiences in the Grand Canyon. The combination of mild temperatures, summer storms, and lush greenery makes it a unique and often overlooked alternative to the hotter, drier South Rim and Inner Canyon.

Inner Canyon: Extreme Heat, Risks of Dehydration and Heatstroke

Summer in the Inner Canyon is an intense and unforgiving experience, characterized by extreme heat, relentless sun exposure, and life-threatening dehydration risks. Unlike the South and North Rims, which benefit from higher elevations and cooling breezes, the Inner Canyon acts as a natural heat trap, absorbing and radiating the sun’s energy throughout the day. For those venturing into the depths of the Grand Canyon during this season, preparation, timing, and caution are critical for survival.

By June, temperatures in the Inner Canyon soar past 100°F (38°C) on most days, with many locations—especially along the Colorado River and Phantom Ranch—regularly exceeding 110°F (43°C) or even 115°F (46°C) in extreme cases. Unlike the rims, where nighttime temperatures offer relief, the Inner Canyon remains oppressively hot even after the sun sets, with overnight lows rarely dropping below 75°F (24°C).

This extreme heat poses significant dangers to hikers, especially those descending from the South or North Rim to the river and back in a single day. The National Park Service strongly discourages attempting such hikes in summer, as the risk of heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and dehydration is dangerously high. Many trails, particularly the Bright Angel and South Kaibab Trails, become hazardous due to intense sun exposure, limited shade, and limited water availability.

One of the greatest risks of summer hiking in the Inner Canyon is dehydration. The low humidity causes sweat to evaporate almost immediately, making it difficult for hikers to recognize how much fluid they are losing. Even experienced hikers can fall victim to heat-related illnesses, and rangers frequently respond to emergencies involving hikers suffering from exhaustion, nausea, and disorientation due to dehydration and overheating.

For those determined to hike in the Inner Canyon during summer, following strict safety guidelines is essential:

- Hike only during the early morning or late afternoon hours. The hottest part of the day (10 AM – 4 PM) should be avoided at all costs.

- Carry more water than expected. The park recommends at least one gallon (4 liters) of water per person per day, though more may be needed depending on exertion levels.

- Electrolyte replacement is critical. Water alone is not enough; salts and minerals lost through sweat must be replenished using sports drinks or electrolyte tablets.

- Wear lightweight, light-colored clothing, a wide-brimmed hat, and sunglasses. Proper gear can help reduce sun exposure and keep the body cooler.

- Take frequent breaks in shaded areas and rest when needed. Overexertion in extreme heat can quickly lead to heatstroke.

The North American Monsoon, which arrives in July and August, introduces another element of danger. While afternoon thunderstorms bring brief temperature drops, they also create flash flooding risks in narrow sections of the canyon. Dry washes and side canyons can transform into raging torrents of water in minutes, sweeping away anything in their path. Hikers caught in these areas during monsoon storms have little to no warning before floodwaters arrive, making awareness of weather forecasts crucial.

Despite the harsh conditions, summer remains one of the most active seasons for river rafting on the Colorado River. Rafters must still take precautions against heat-related illnesses, but the river provides an opportunity to stay cool while experiencing some of the most dramatic landscapes within the canyon. Many rafters also use the side canyons and hidden waterfalls to escape the midday heat, taking advantage of the rare oases of cooler air and fresh water.

Wildlife in the Inner Canyon is largely nocturnal during summer, as most animals retreat to shady areas or burrows to escape the heat. Bighorn sheep, lizards, and ringtail cats remain active, but many mammals, including foxes and smaller rodents, only emerge after sunset. Birds such as turkey vultures and ravens take advantage of the warm air currents, soaring high above the canyon floor in search of food.

For those who do attempt hiking or backpacking in the Inner Canyon during summer, the stakes are high, but the rewards are undeniable. Dramatic sunrises and sunsets, the glowing red canyon walls, and the solitude of less-crowded trails offer an unparalleled experience. However, extreme caution, preparation, and respect for the desert environment are required to safely navigate this unforgiving landscape.

As August comes to an end, the worst of the summer heat begins to gradually subside, paving the way for cooler fall temperatures and the return of safer hiking conditions.

Fall (September – November)

South Rim: Cooling Temperatures, Fall Foliage, Reduced Visitor Numbers

Fall at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon is one of the most beautiful and pleasant seasons to visit. As the intense summer heat fades, temperatures gradually drop, making outdoor activities more comfortable while still allowing for long daylight hours. The crowds of summer begin to thin, and the landscape transforms as fall foliage brings bursts of golden yellow and deep red hues to the high-elevation forests.

In September, the South Rim remains warm during the day, with highs ranging from 70°F to 80°F (21°C to 27°C). However, nighttime temperatures begin to dip into the 40s°F (4°C to 10°C), providing crisp, cool evenings perfect for camping and stargazing. Unlike the summer months, when hiking during midday was dangerous due to extreme heat, fall allows for longer, safer hiking windows throughout the day.

By October, temperatures continue to decline, averaging highs of 60°F (15°C) and lows around freezing. This is also the peak time for fall foliage, as the aspen and oak trees near the rim turn vibrant shades of yellow and orange, contrasting against the canyon’s red and brown rock formations. Photographers and nature enthusiasts flock to areas like Desert View and Yaki Point, where the changing leaves create a stunning visual contrast against the deep blue autumn skies.

November brings the first signs of winter, with daytime temperatures dropping further to 50°F (10°C) and nighttime lows often falling below freezing. Snowfall is rare but possible in late November, and strong winds can make conditions feel colder than the actual temperature. Many services and accommodations start to scale down operations for the winter season, and visitor numbers significantly decrease compared to the peak months of summer.

One of the greatest advantages of visiting the South Rim in the fall is the reduction in crowds. While September still sees a moderate number of visitors, by October and November, the park is much quieter, allowing for a more serene experience at viewpoints, on hiking trails, and around Grand Canyon Village.

Wildlife is also particularly active in the fall, as mule deer, elk, and smaller mammals prepare for the colder months ahead. Elk rutting season peaks in September and early October, meaning visitors may witness male elk engaging in dramatic mating battles, locking antlers in displays of dominance. Bird migration also increases, with species such as hawks and eagles soaring over the canyon in preparation for their journey southward.

For hikers and adventurers, fall is one of the best seasons to explore the Grand Canyon, as it offers the perfect blend of comfortable temperatures, clear skies, and fewer crowds. Whether hiking the Bright Angel Trail, exploring Hermit’s Rest, or simply taking in the views from the rim, fall provides an exceptional and peaceful experience at the canyon’s most famous locations.

As November draws to a close, winter’s approach becomes evident, with colder mornings, frost on the trails, and the occasional snowfall dusting the high plateaus. The transition from fall to winter marks the end of the most comfortable hiking season, setting the stage for the quiet, snowy months ahead.

North Rim: First Snowfalls, Closure Preparations

Fall at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon is a fleeting but spectacular season, bringing cooler temperatures, vibrant fall foliage, and the first signs of winter. Because of its high elevation (8,000 feet / 2,440 meters), the North Rim experiences fall much earlier than the South Rim or the Inner Canyon. By late September, temperatures drop significantly, and by mid-October, the first snowfalls can occur, marking the beginning of the seasonal transition toward winter closure.

In September, daytime temperatures at the North Rim hover around 65°F to 75°F (18°C to 24°C), with nighttime lows dipping into the 30s°F (0°C to 4°C). While the temperatures are still comfortable for hiking and sightseeing, visitors should be prepared for chilly mornings and evenings. Fall colors begin appearing in early to mid-September, with the aspen trees turning brilliant shades of gold, creating breathtaking scenery along the North Rim’s meadows and trails.

October is when fall fully takes hold at the North Rim. By this time, temperatures rarely exceed 60°F (15°C) during the day, and nighttime lows frequently drop below freezing. The landscape begins to shift toward winter, as strong winds strip the last leaves from the trees, and wildlife prepares for the harsh months ahead.

This is also when the first snowfalls of the season begin. While early October may see only light dustings of snow, by the end of the month, heavier storms can occur, covering the roads, trails, and forests in a layer of white. The arrival of snow is a key signal that the North Rim is preparing to close for the winter.

The North Rim officially closes to visitors on or around November 1st, as the National Park Service shuts down all lodges, visitor services, and accommodations for the season. Highway 67, the only road providing access to the North Rim, is not plowed in winter, meaning that once snowfall becomes consistent, access is limited to those using snowshoes or cross-country skis.

During these final weeks before closure, the North Rim becomes an incredibly quiet and remote place, offering one of the most serene experiences in the entire Grand Canyon. Visitor numbers drop significantly compared to the summer months, and those who make the trip during late October can enjoy the views without crowds, experiencing the Grand Canyon in a more peaceful, almost mystical state as it transitions from fall into winter.

Wildlife at the North Rim is also highly active in the fall, as many species prepare for the arrival of colder weather. Mule deer and elk become more visible, gathering in larger herds as they begin their seasonal migration to lower elevations. Black bears, which are rarely seen during the summer months, are more active in fall, foraging heavily before entering hibernation in November. Bird activity increases as well, with hawks, eagles, and other raptors seen migrating south before the first major storms of winter arrive.

For those who visit in late September or early October, hiking is still possible, but extra caution is required. As temperatures drop and snow begins to accumulate, trails can become icy and dangerous, particularly steep routes like the North Kaibab Trail that descend into the canyon. Hikers should dress in layers, carry traction devices for icy conditions, and prepare for sudden temperature drops.

By the time November arrives, the North Rim is virtually deserted, with snow covering the high plateaus and forests. The official closure marks the end of the season, and for the next six months, the North Rim will remain inaccessible to most visitors, awaiting the return of spring’s thaw in May.

For those seeking solitude, breathtaking fall foliage, and a glimpse of the Grand Canyon’s wilder, less-traveled side, visiting the North Rim in fall is an unforgettable experience. However, travelers should always check road conditions and weather forecasts before setting out, as early storms can accelerate closures and make travel challenging.

Inner Canyon: Gradual Temperature Decline, Optimal Hiking Conditions

Fall in the Inner Canyon marks the end of the brutal summer heat and the beginning of one of the best seasons for hiking and exploration. As temperatures gradually cool, the risks of heat exhaustion and dehydration lessen, making September through November the prime months for long-distance trekking, river rafting, and backpacking adventures.

By early September, temperatures in the Inner Canyon remain warm, with daytime highs still reaching 90°F to 100°F (32°C to 38°C). However, unlike in summer, the nights begin to cool down significantly, often dropping into the mid-60s°F (18°C), making evenings much more comfortable for camping and sleeping outdoors. The transition from day to night becomes more pronounced, and hikers can take advantage of longer, cooler mornings before the midday sun becomes too intense.

As October arrives, the Inner Canyon experiences more noticeable relief from the heat, with daily highs ranging from 80°F to 90°F (27°C to 32°C) and nighttime temperatures dropping into the 50s°F (10°C to 15°C). This is the time when hiking conditions are at their absolute best, as the days remain warm but not dangerously hot, and seasonal water sources are still available along the trails. Rafting trips along the Colorado River are also at their peak, as the river maintains strong flow rates from late-summer snowmelt while the weather becomes more comfortable for long days on the water.

Wildlife in the Inner Canyon becomes more active in fall, as cooler temperatures allow animals that had been hiding from the summer sun to roam more freely. Bighorn sheep can be spotted along the rocky cliffs, mule deer frequent the areas near the river, and desert reptiles, such as lizards and Gila monsters, remain visible during the warm afternoons. Birdwatchers also notice an increase in migratory species, as hawks and eagles move south, taking advantage of the canyon’s updrafts to glide along the thermals with little effort.

By November, temperatures in the Inner Canyon drop even further, with daytime highs averaging 65°F to 75°F (18°C to 24°C). Nighttime temperatures, however, can dip into the 40s°F (4°C to 10°C), and even lower in shaded areas near the river, making warm clothing essential for overnight campers at Phantom Ranch or Bright Angel Campground.

As the season progresses, water availability begins to change. Seasonal creeks that were fed by monsoon rains in late summer start to dry up, making water planning more critical for long-distance hikers. Although major sources such as Bright Angel Creek and the Colorado River remain reliable, those trekking on less-traveled routes must be aware that some springs may no longer be flowing by late fall.

By the end of November, the Inner Canyon enters its winter phase, with crisp mornings, shorter daylight hours, and more dramatic shifts between daytime warmth and nighttime cold. While the harsh summer sun is gone, hikers must now prepare for cooler conditions, icy patches in shaded areas, and unpredictable weather shifts.

For those looking for the ultimate Grand Canyon hiking experience, fall in the Inner Canyon is one of the best times to visit. The combination of cooler temperatures, minimal crowds, and stunning scenery makes it a favorite season among seasoned backpackers and outdoor enthusiasts. Unlike the North Rim, which shuts down for winter, the Inner Canyon remains accessible year-round, allowing those who plan properly to enjoy one of the most breathtaking landscapes in the world without the summer’s deadly heat or winter’s extreme cold.

By the time fall gives way to winter, the Inner Canyon has fully transitioned into its cooler season, with more comfortable hiking conditions and fewer visitors, offering a quiet, peaceful experience for those willing to explore its depths.

Temperature Variations from Rim to River

The Grand Canyon’s immense elevation range—from the snowy North Rim at over 8,000 feet (2,440 meters) to the scorching depths of the Colorado River at just 2,000 feet (610 meters)—creates one of the most extreme vertical climate gradients on Earth. Temperature differences between the rim and the river can exceed 30°F (16.7°C) on any given day, leading to drastic weather variations that affect hiking conditions, wildlife behavior, and plant distribution throughout the canyon.

This chapter explores how temperature shifts with elevation, how day-night fluctuations impact different areas, and how climate change is influencing these long-term trends.

3.1. The Vertical Climate Gradient

One of the most defining aspects of Grand Canyon weather is the vertical temperature gradient—the difference in temperature between the canyon’s highest and lowest points. In general, for every 1,000 feet (305 meters) of elevation change, the temperature shifts by approximately 5.5°F (3°C). This means that the North Rim can be experiencing snow and freezing temperatures while the Inner Canyon bakes under triple-digit heat at the very same time.

For example, on a typical summer day in July, conditions across the canyon can vary dramatically:

- North Rim: 65°F (18°C), cool and comfortable, with afternoon storms possible.

- South Rim: 80°F (27°C), warm but manageable, with strong sunshine.

- Inner Canyon (Phantom Ranch): 110°F (43°C), dangerously hot, requiring extreme caution for hikers.

This stark contrast between cool high-altitude conditions at the rims and the desert-like climate of the canyon floor means that hikers and outdoor adventurers must prepare for multiple climate zones in a single day. Someone hiking from the North Rim to the river may experience an environmental shift equivalent to traveling from Canada to Mexico in just a few hours.

While summer produces the most extreme temperature differences, winter is no exception. In January, it is common to see:

- North Rim: 20°F (-7°C) or lower, with heavy snowfall.

- South Rim: 35°F (2°C), with occasional snow and ice.

- Inner Canyon: 60°F (16°C) and mild, perfect for winter hiking.

These temperature differences are critical for hikers, rafters, and campers, as failing to account for the rapid temperature change between elevations can lead to dangerous situations, including heatstroke in the summer or hypothermia in the winter.

3.2. Diurnal Temperature Swings

In addition to the vertical climate gradient, another important factor in Grand Canyon weather is diurnal temperature variation, or the difference between daytime highs and nighttime lows. Due to low humidity and clear desert skies, the Inner Canyon experiences some of the most extreme day-night temperature swings found anywhere in North America.

During the summer months, the Inner Canyon can reach 110°F (43°C) during the day, but temperatures can plummet to 70°F (21°C) or lower at night. This means that a hiker dressed for scorching heat at noon may find themselves shivering by midnight if they are not properly prepared.

This extreme diurnal variation is caused by several key factors:

- Lack of moisture in the air – Without humidity to trap heat, the warmth from the sun dissipates rapidly after sunset.

- Thermal absorption and release from canyon walls – The rock formations absorb solar energy during the day and release it at night, affecting temperatures near canyon walls.

- Altitude-related pressure differences – The dense, low-lying air of the Inner Canyon allows for faster heating and cooling than the thinner air at the rims.

In contrast, the North Rim and South Rim experience less extreme day-night swings due to higher humidity, tree cover, and lower overall temperatures. However, even at the rims, nighttime temperatures can be significantly colder than expected, catching some visitors off guard.

Understanding these drastic day-night shifts is essential for planning overnight hikes and backcountry camping trips, as hikers must pack layers to accommodate both extreme heat and cold.

3.3. Historical Temperature Trends and Climate Change Impact

Over the past several decades, long-term climate data from the Grand Canyon suggests that temperatures are gradually increasing, particularly in the higher elevations. Climate change models indicate that the rims are warming at a faster rate than the Inner Canyon, which could have significant ecological and environmental consequences.

Historical Temperature Data

Weather stations at the South Rim, North Rim, and Phantom Ranch have recorded temperature fluctuations for over 100 years, showing noticeable trends in warming winters and longer hot periods during summer.

- Winters are becoming milder, with fewer days of extreme cold at the North and South Rims.

- Summers are lasting longer, with heat waves extending into late September and even October in recent years.

- Monsoon patterns are shifting, bringing less predictable rainfall and more erratic storm behavior.

Impact on Ecosystems and Wildlife

These temperature changes are affecting wildlife migration, plant distribution, and water availability throughout the canyon.

- The North Rim’s pine forests are seeing earlier snowmelt and longer dry seasons, increasing the risk of wildfires.

- Desert animals in the Inner Canyon, such as bighorn sheep and reptiles, are facing hotter summers, which can affect their water sources and breeding patterns.

- Seasonal water sources that once flowed reliably throughout the canyon are drying up earlier in the year, posing challenges for hikers and wildlife alike.

The Future of Grand Canyon Weather

Scientists predict that if current warming trends continue, the Grand Canyon will experience:

- More extreme summer heat, with 120°F (49°C) days in the Inner Canyon becoming more common.

- Shorter, warmer winters, with less snow accumulation at the rims.

- Longer dry seasons and more erratic monsoonal rain patterns, leading to increased flash flooding risks.

For future visitors, these changes mean that hiking conditions could become even more extreme, requiring greater preparation and awareness of weather hazards. Park officials are already adjusting guidelines for summer hiking safety, increasing warnings about heat-related illnesses, and encouraging more education on monsoon dangers and hydration planning.

The Role of Precipitation and Hydrology

The Grand Canyon’s water cycle is as complex and varied as its landscapes. While many visitors envision the canyon as an arid desert environment, precipitation plays a crucial role in shaping its climate, ecosystems, and geological formations. The interaction of rainfall, snowfall, monsoons, and underground water systems influences not only the plants and animals that thrive in different elevations but also the experiences of hikers, rafters, and researchers studying the region.

Water has been the primary force behind the formation of the Grand Canyon, carving through rock over millions of years. However, it remains an unpredictable and sometimes dangerous element in the canyon’s modern landscape. While the North Rim receives abundant snowfall and seasonal rain, the Inner Canyon and South Rim are often dry, with water sources that are highly seasonal or even unreliable. Flash floods, monsoon storms, and long droughts all contribute to the canyon’s dynamic hydrology, making water a critical factor for survival and environmental stability.

This chapter explores the different precipitation patterns that affect the Grand Canyon, from the snowfall that blankets the North Rim in winter to the intense monsoon storms that reshape the canyon’s inner depths in summer.

4.1. Rainfall Patterns Across the Grand Canyon

Precipitation in the Grand Canyon is highly variable and dependent on elevation. The North Rim receives the highest annual rainfall and snowfall, while the Inner Canyon remains one of the driest regions in the western United States. This variation is due to topographic influences, atmospheric moisture patterns, and seasonal climate shifts.

The North Rim, at over 8,000 feet (2,440 meters) above sea level, receives an average of 27 inches (69 cm) of precipitation per year. This includes significant winter snowfall, which contributes to seasonal water availability as it melts in the spring.

The South Rim, located at 7,000 feet (2,100 meters), receives an average of 16 inches (41 cm) of precipitation annually, much of which comes in the form of rain during summer monsoons and snow in winter. This moderate level of precipitation allows for the presence of hardy conifer forests but is still insufficient to create the kind of lush greenery seen at similar elevations in wetter regions.

The Inner Canyon, by contrast, is extremely arid, receiving less than 10 inches (25 cm) of annual rainfall. The lack of precipitation in the Inner Canyon creates true desert conditions, with cacti, dry washes, and extreme temperature variations dominating the landscape. The limited rainfall also means that many water sources are seasonal, forcing wildlife and hikers alike to rely on permanent water sources like the Colorado River.

These precipitation patterns are not only a function of elevation but also of the broader climate systems affecting the region, including the North American Monsoon and the rain shadow effect.

4.2. Snowfall and Snowmelt Dynamics

Snowfall is a defining feature of winter at the Grand Canyon, particularly at the higher elevations of the North and South Rims. The amount of snowfall varies greatly depending on location, but it plays a critical role in seasonal water storage, springtime water availability, and long-term canyon erosion.

The North Rim receives the heaviest snowfall, averaging up to 144 inches (365 cm) per year. This heavy snowpack is essential for replenishing seasonal water sources, as the snowmelt in spring feeds streams and springs throughout the canyon. However, it also leads to road closures and restricted access, as the North Rim remains inaccessible for nearly half the year due to deep snow accumulation.

The South Rim receives significantly less snowfall, averaging 60 inches (152 cm) annually. While this is still enough to create a winter wonderland effect, the snowpack is less consistent and melts more quickly in the spring. This leads to muddy trail conditions on popular routes like Bright Angel and South Kaibab Trails, where melting snow contributes to slippery, challenging terrain in March and April.

At lower elevations, including the Inner Canyon, snowfall is rare. While it is possible to see light snow flurries at Phantom Ranch on occasion, the warmer temperatures at lower elevations prevent significant accumulation. Instead, the Colorado River remains a stable source of water year-round, sustained by both snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains upstream and precipitation from within the canyon itself.

Snowmelt is one of the most important hydrological processes in the Grand Canyon, as it replenishes seasonal streams and groundwater reserves, ensuring that wildlife, vegetation, and hikers have access to water throughout the year. However, in recent years, climate change has led to reduced snowpack levels, resulting in earlier and less predictable spring melt cycles.

4.3. The Colorado River’s Response to Climatic Variations

The Colorado River is the lifeblood of the Grand Canyon, shaping its landscapes over millions of years and providing essential water for both natural ecosystems and human activities. However, the river’s flow, temperature, and seasonal behavior are heavily influenced by precipitation patterns, snowmelt cycles, and human interventions upstream.

Seasonal Changes in River Discharge

The Colorado River’s flow rate fluctuates throughout the year, largely depending on snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains and precipitation within the canyon.

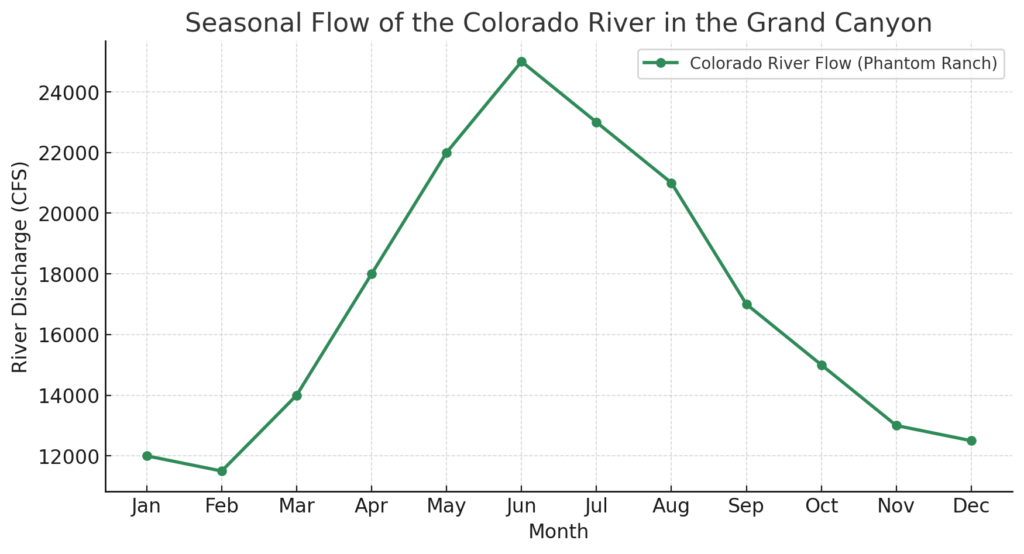

- In spring (March – June), melting snow from the Rocky Mountains and high plateaus of the Colorado River Basin increases water levels, creating stronger currents and higher discharge rates.

- During summer (July – September), monsoon storms can cause sudden spikes in water levels, leading to flash flooding in tributary streams and temporarily increasing the river’s flow.

- In fall and winter (October – February), water levels tend to be lower and more stable, as precipitation decreases and upstream reservoirs regulate flow more consistently.

These seasonal shifts directly impact rafting conditions, water accessibility for hikers, and sediment transport, which continues to shape the canyon’s evolving landscape.

Impact of Temperature and Precipitation on Water Availability

The availability of fresh water in the Grand Canyon is a growing concern, as climate change, upstream water diversions, and regional droughts reduce the river’s flow. Over the past several decades:

- The Colorado River’s average flow rate has declined due to reduced snowfall in the Rocky Mountains and increased water demand from growing populations in the Southwest.

- The temperature of the river has increased, affecting fish populations and aquatic ecosystems. Species such as the humpback chub, which evolved to thrive in colder water, are now facing survival challenges due to rising water temperatures.

- Seasonal water sources within the canyon, including springs and creeks, are drying up earlier in the year, making it more difficult for hikers and wildlife to find reliable drinking water.

As climate trends continue to shift, understanding the long-term hydrological changes in the Grand Canyon will be critical for conservation efforts, sustainable water management, and the survival of the canyon’s ecosystems.

Weather Hazards and Safety Considerations

The Grand Canyon’s diverse and extreme weather conditions make it one of the most beautiful yet hazardous natural environments in the world. The same forces that shape the canyon’s landscapes—intense heat, sudden storms, and steep elevation changes—also create serious risks for visitors. Each year, hundreds of hikers, rafters, and sightseers encounter dangerous situations due to heat-related illnesses, flash floods, lightning strikes, and winter storms.

While proper planning, awareness, and preparation can prevent most accidents, the canyon’s weather is unpredictable, and even experienced adventurers must respect its challenges. This chapter explores the most significant weather hazards in the Grand Canyon, their causes, and how visitors can stay safe while exploring this extreme landscape.

5.1. Heat Dangers in the Inner Canyon

The Deadly Reality of Heatstroke and Dehydration

One of the greatest dangers in the Grand Canyon is extreme heat, particularly in the Inner Canyon during summer. Temperatures at the bottom of the canyon can soar above 110°F (43°C) in the shade, and hiking trails offer little protection from the relentless sun.

Many visitors underestimate how quickly dehydration and heat exhaustion can set in. Unlike in humid environments, where sweating is more noticeable, the dry desert air causes sweat to evaporate instantly, making it harder for hikers to recognize how much water they are losing. By the time symptoms of dehydration appear—such as dizziness, nausea, and muscle cramps—hikers may already be in danger.

Recognizing and Preventing Heat-Related Illnesses

There are three main stages of heat-related illness:

- Heat exhaustion – Symptoms include heavy sweating, dizziness, nausea, headache, and fatigue. Without intervention, it can quickly lead to heatstroke.

- Heatstroke – A life-threatening emergency where the body’s temperature regulation fails. Symptoms include confusion, rapid heartbeat, and lack of sweating. If untreated, heatstroke can cause organ failure and death.

- Hyponatremia (Overhydration) – Drinking too much water without replacing electrolytes can dilute sodium levels in the blood, leading to seizures and unconsciousness.

To prevent heat-related illnesses, hikers should follow these essential safety guidelines:

- Hike early or late – Avoid hiking between 10 AM and 4 PM, the hottest part of the day.

- Stay hydrated, but balance fluids – Drink at least a gallon (4 liters) of water per day, but also consume salty snacks or electrolyte supplements to prevent overhydration.

- Wear protective clothing – Light-colored, moisture-wicking clothing, a wide-brimmed hat, and sunglasses help protect against the sun.

- Take frequent breaks in the shade – Rest whenever possible to avoid overheating.

- Know your limits – The hike down is optional, but the hike up is mandatory—many heat-related rescues occur because hikers underestimate the difficulty of climbing back up the canyon.

The Park Service strongly discourages hiking from rim to river and back in a single day during summer due to the high number of medical emergencies and fatalities that occur each year.

5.2. Monsoon Season and Flash Flooding

The Power and Danger of Sudden Floods

From July to September, the North American Monsoon brings intense thunderstorms to the Grand Canyon, often developing within minutes and producing heavy rain, lightning, and flash floods. While the rims receive most of the rainfall, the steep canyon walls funnel this water into dry washes and slot canyons, turning them into raging torrents of water with little warning.

Flash floods are one of the most underestimated dangers in the Grand Canyon. Even if the sky is clear where a hiker is standing, rainfall miles away can cause an upstream flood that arrives with incredible force, carrying debris, boulders, and tree trunks downstream. These floods are powerful enough to destroy trails, sweep away hikers, and reshape canyon landscapes in minutes.

How to Stay Safe During Monsoon Season

- Check the weather forecast – Always be aware of thunderstorm predictions before hiking in the canyon.

- Avoid narrow slot canyons and washes – Areas like Havasu Canyon and Kanab Creek are particularly dangerous during monsoon season.

- Look for warning signs – Sudden changes in wind, dark clouds forming overhead, and distant thunder are early indicators of a storm.

- Seek higher ground immediately – If you hear roaring water or see rising water levels, move to higher ground immediately—even just a few feet can save your life.

- Be aware of debris flow – Flash floods often carry large rocks, logs, and mud, making them extremely dangerous even if the water level seems shallow.

While the monsoon season brings spectacular lightning displays and temporary waterfalls, it also creates serious hazards for hikers and rafters, making preparation and caution essential.

5.3. Winter Storms and Hypothermia Risks

Snow, Ice, and Freezing Temperatures at the Rims

Winter at the North and South Rims can be harsh and unpredictable, with snowstorms, ice-covered trails, and subzero temperatures creating dangerous conditions for visitors. While the Inner Canyon remains relatively mild, the rims can experience heavy snowfall, high winds, and sudden weather changes.

Dangers of Winter Hiking and Driving

- Icy Trails – The Bright Angel and South Kaibab Trails become extremely slippery in winter, requiring crampons or traction devices for safe hiking.

- Frostbite and Hypothermia – Exposure to cold winds and freezing temperatures without proper gear can lead to life-threatening hypothermia.

- Road Closures – The North Rim is closed from mid-November to mid-May due to deep snow, and even South Rim roads can be temporarily shut down after heavy snowfall.

How to Stay Safe in Winter

- Wear insulated layers – Dressing in multiple layers, including waterproof outer gear, prevents heat loss.

- Carry traction devices – Microspikes or crampons help prevent slipping on icy trails.

- Check road and trail conditions – Park rangers provide updates on closures and dangerous trail conditions.

- Start hikes early – Winter daylight hours are shorter, and finishing hikes before sunset is crucial.

For those prepared for winter conditions, the Grand Canyon in snow offers breathtaking scenery, but it requires the right equipment and planning to avoid dangerous exposure risks.

Ecological and Wildlife Adaptations to Climate

The Grand Canyon’s extreme climate variations—from the snow-covered North Rim to the scorching depths of the Inner Canyon—have shaped a rich and diverse ecosystem of plants and animals. With elevation differences of over 6,000 feet (1,800 meters), daily temperature swings exceeding 30°F (16.7°C), and highly variable rainfall patterns, survival in the canyon requires extraordinary adaptations.

Plants and animals in the Grand Canyon have evolved over thousands of years to cope with harsh summers, freezing winters, limited water sources, and erratic weather patterns. Some species migrate with the seasons, others hibernate, and many have developed specialized physiological and behavioral traits that allow them to thrive in this ever-changing environment.

This chapter explores the incredible adaptations of the Grand Canyon’s plant and animal life, highlighting how they respond to temperature fluctuations, water availability, and seasonal climate changes.

6.1. Plant Adaptations to Temperature Extremes

The Grand Canyon supports a wide variety of plant life, from alpine forests at the rims to drought-resistant cacti in the Inner Canyon. The types of vegetation found at different elevations are heavily influenced by temperature, precipitation, and soil composition.

North Rim: Cold-Tolerant Conifers and Seasonal Wildflowers

The North Rim, with its high elevation (8,000+ feet / 2,440+ meters), heavy snowfall, and short growing season, supports hardy, cold-tolerant plants. Dense forests of ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and Engelmann spruce dominate the landscape, forming an ecosystem more typical of the Rocky Mountains than the desert Southwest.

To survive long, harsh winters, many of these trees have thick bark that insulates them from freezing temperatures. Additionally, some species, like the quaking aspen, are adapted to survive wildfires by regenerating from underground root systems after a burn.

Wildflowers, including lupines, paintbrush, and columbine, take advantage of the short summer growing season, blooming quickly in late spring and early summer before the first snowfalls of October.